All text, translations, and maps copyrighted by Lawrence Douglas Ringer. Last modified on: 08-September-2015.

If you encounter a word or spelling with which you are unfamiliar, be sure to check the glossaries (see the links on the right under Reference Aids).

You may find the following timeline useful. If you have a large enough screen, I suggest that you place the timeline window side by side with this window. To open the timeline in a separate window on a Mac, hold down the ‘Control’ key while clicking on the link.

During the Greek Classical Age (ca. 500–323 BCE), there were two famous battles fought in the vicinity of the Arkadian city of Mantinea.[1] The first was a Lakedaimonian (Spartan) victory over a coalition consisting of the Argives, Athenians, and Mantineans in 418 BCE during the Peloponnesian War. The victorious commander was the Lakedaimonian king Agis II (reigned 427/426–401/400 BCE). (Thoukydides. 5.64–74)

The second famous battle fought near Mantinea was a victory by the Thebans and their allies in 362 BCE. The victorious general was Epameinondas of Thebes. His opponents were the the Lakedaimonians (Spartans), Athenians, Eleians, Akhaians, Mantineans, and a few other Arkadians.

The ancient accounts of this latter campaign are diverse and contradictory as are the modern retellings. The narrative of Xenophon of Athens in the Hellēnika is the only contemporary account and is also by far the most detailed account. It was, moreover, a record of military operations by an experienced military man. In addition, Xenophon was closely associated with both the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) and Athenians, two of the losing participants in the battle of Mantinea. Xenophon was a lover of all things Spartan and was a long-time acquaintance of the elderly Lakedaimonian king Agesilaos II (reigned ca. 401/400–360/359 BCE), the younger half-brother of Agis II. It is noteworthy that Xenophon’s two sons—Gryllos and Diodoros—were both educated in Lakedaimon (Sparta) and both also fought in the Athenian army at the battle of Mantinea. As a result of all of these factors, Xenophon would have had first hand knowledge of many details that would have been unknown to later historians. Unfortunately, due to his blatant partisanship on behalf of oligarchs and Lakedaimon (Sparta), Xenophon is notorious for his omissions and also for his biased assessments. The historical ‘facts’ that Xenophon recorded are nonetheless rarely contested. Therefore, I have for the most part followed Xenophon’s version of the events.[2]

In 371 BCE—nine years prior to the battle of Mantinea—the Thebans had decisively defeated the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) at the battle of Leuktra in Boiotia. The Thebans were led by Epameinondas, who was one of the Boiotarchs, and by Pelopidas, who was the commander of the 300 man Theban Sacred Band.[3] The battle of Leuktra was decisive in the sense that it forever shattered the myth of Lakedaimonian (Spartan) invincibility and also inflicted a severe blow to Lakedaimonian manpower. Though it was not immediately obvious, the battle of Leuktra in 371 BCE would sound the death knell for the Lakedaimonian hegemony of Greece. On the other hand, the battle of Mantinea in 362 BCE would not be nearly as decisive on the battlefield itself and yet it would mark the end of Lakedaimon (Sparta) as a major power, a process that had begun in earnest at Leuktra.

In the years immediately following the momentous Lakedaimonian (Spartan) defeat at Leuktra, many former Lakedaimonian allies defected to the victorious Thebans. It was this loss of so many of their allies and subjects—who were no longer in awe and fear of the ‘invincible’ Spartans—that eventually brought an end to the era of Lakedaimonian hegemony. Ironically, the Lakedaimonians did gain one major new ally: Athens. The Athenians had been defeated by the Lakedaimonians in the Peloponnesian War (ca. 431–404 BCE), but in 371 BCE they were fearful of the growing power of nearby Thebes and allied with the Lakedaimonians in hopes of maintaining a balance of power. As for the early Peloponnesian defectors from the Lakedaimonians, the two most prominent were the Eleians and Arkadians.

THE ELEIANS AND LAKEDAIMONIAN IMPERIALISM

In ca. 399–397 BCE—nearly three decades prior to the battle of Leuktra—the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) had invaded Eleia (the homeland territory of Elis) and had ‘liberated’ many of the towns of Triphylia and Eleia from Eleian jurisdiction. The war had begun when the Eleians had banned the Lakedaimonians from the Olympic Games—perhaps the 95th Olympics in 400 BCE—due to some unknown adjudication against the Lakedaimonians. The Eleians had also offended the Lakedaimonians by preventing the Lakedaimonian king Agis II from sacrificing to Zeus at Olympia. The Eleians claimed that it was contrary to custom for them to allow a sacrifice on behalf of a victory against other Greeks. All in all, the Lakedaimonians considered that the Eleians had become far too independent-minded following the end of the Peloponnesian War (ca. 431–404 BCE) and had forgotten their subservient relationship. The Lakedaimonians, therefore, had punished the Eleans by stripping them of much of their territory and had forced them to once again become obedient Lakedaimonian allies.[4] (Xenophon. Hellēnika 3.2.23–31)

After the Lakedaimonian (Spartan) defeat in the battle of Leuktra, the Athenians brokered a peace treaty in late 371 BCE. As a result of their loss of territory in ca. 399–397 BCE, the Eleians declined to sign this treaty as it preserved the status quo. The Eleians instead reaffiirmed their claim to ownership of Marganeis, Skillous, and Triphylia and consequently refused to recognize their autonomy under the terms of this common peace. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.5.1–3)

THE ARKADIANS AND LAKEDAIMONIAN IMPERIALISM

At the conclusion of the Korinthian War (ca. 395–386 BCE), the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) decided to make an example of the Arkadian city of Mantinea in order to deter their allies from thoughts of independence. The Mantineans had incurred the Lakedaimonians’ displeasure by sending grain to Argos while the Argives were at war with Lakedaimon and also by claiming that they could not serve in several Lakedaimonian campaigns due to an ekekheiria (armistice or holiday). Additionally, when the Mantineans did join in Lakedaimonian expeditions, the Lakedaimonians considered that the Mantineans were serving poorly. In 385 BCE—fourteen years prior to the battle of Leuktra—the Lakedaimonian king Agesipolis I (reigned 395–380 BCE) besieged Mantinea and compelled the Mantineans to surrender by diverting a river against the city’s walls. The Lakedaimonians then forcibly subjected the Arkadians of Mantinea to dioikismos (dispersal to villages) and exiled their democratic leaders, whom Xenophon called “troublesome demagogues”. This was done in contravention of the King’s Peace of 386 BCE, which had guaranteed autonomy to each and every Greek city and for which the Lakedaimonians themselves had been the prime movers! (Xenophon. Hellēnika 5.2.1–7; Diodoros. 15.5, 15.12)

Incidentally, Pelopidas and Epameinondas were two young Thebans—both probably around 30 years old—dutifully serving as hoplites in the Lakedaimonian allied army during the attack on Mantinea by Agesipolis in 385 BCE. In the fighting, Epameinondas was said to have saved the life of his friend Pelopidas. (Plutarch. Pelopidas 4.4–5)

Following the Lakedaimonian (Spartan) defeat at Leuktra in 371 BCE, the Mantineans took the opportunity to reverse their humiliation at the hands of the Lakedaimonians. The Mantineans synoikized (merged from villages into a city) and—despite the not so veiled threats of the Lakedaimonian king Agesilaos—began to build city walls. These actions were designed to ensure their autonomy by giving the Mantineans the ability to defend themselves from behind fortifications. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.5.3–5)

Mantinea, incidentally, was one of the two most important cities of Arkadia. The other was Tegea in southeastern Arkadia. While the Mantineans were busy rebuilding their city, the Tegeatan democrats siezed power in Tegea with the assistance of the Mantineans and executed the pro-Lakedaimonian oligarchs of Tegea. Their remaining aristocratic followers fled into exile to Lakedaimon. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.5.6–9)

At the same time, many of the Arkadians began to organize with the intention of forming a democratic koinon (league). The Arkadians who were so inclined gathered together at Asea on Arkadia’s southern border. This democratic movement was a major threat to Lakedaimonian (Spartan) control, which was based on supporting oligarchies and preventing the formation of larger states. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.5.6–12)

THE ELEIANS, ARKADIANS, AND ARGIVES JOIN FORCES AGAINST THE LAKEDAIMONIANS, 370 BCE

In response to these events, the Lakedaimonian (Spartan) king Agesilaos invaded Arkadia in late 370 BCE on the absurd pretence that the Mantineans had violated the peace by interfering in the civil war in Tegea. Agesilaos advanced to Mantinea and was shadowed by the nascent Arkadian League army from Asea. At Mantinea, Agesilaos was unable to prevent this army from joining forces with the Mantineans along with troops from Elis and Argos. If it had not been clear before, it would have been perfectly clear at this point that the Eleians had renounced their alliance with the Lakedaimonians. Having taken up arms against the Lakedaimonians, this may have been the moment when the Eleians reclaimed at least some of their lost territories. As for Argos, it was the lone Peloponnesian state to have always maintained its independence and opposition to the Lakedaimonians. As a result, the democratic Argives no doubt joined this anti-Lakedaimonian alliance with unmitigated zeal. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.5.5, 6.5.10–12, 6.5.15–16, 6.5.19)

The Lakedaimonian (Spartan) army was reinforced by Arkadians from Heraia and Orkhomenos (a traditional enemy of nearby Mantinea) as well as Lepreatans from Triphylia and Phleiasians. However, the Eleians, Argives, and the Arkadian democrats wisely refused to give battle as they had—belatedly it would appear—summoned the Thebans to come to their aid and were awaiting their arrival. When Agesilaos realised this and considered that it was already winter, he withdrew back home as quickly as he could without his withdrawal looking like flight. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.5.11, 6.5.17–22)

THE FIRST THEBAN CAMPAIGN INTO THE PELOPONNESOS, 370/369 BCE

In the winter of 370/369 BCE, the Thebans arrived in the Peloponnesos with a large allied army from central Greece. The Thebans had spent the year following the battle of Leuktra consolidating a new coalition amongst the Boiotians, Phokians, Euboians, both (i.e. eastern and western) Lokrians, Akarnanians, Herakleots, Malians, and Thessalians. Once they arrived in the Peloponnesos, the ranks of the Theban allied army were swelled by the Eleians, Arkadians, and Argives. This massive Theban allied army then invaded Lakonike, the homeland of the Lakedaimonians (Spartans). The Theban Boiotarchs Epameinondas and Pelopidas—the victors of the battle of Leuktra in 371 BCE—were at first reluctant to invade Lakonike, but were persuaded to do so by their Peloponnesian allies as well as by some of the Lakedaimonian perioikoi (second-class citizens). This invasion was an historic event as Lakonike had not been invaded within human memory. The Arkadians, Eleians, Argives, and Thebans each led one of the four columns that invaded Lakonike. The Arkadians annihiliated the Lakedaimonian force that attempted to block their advance at Oion in Skiritis and thereby emboldened the Theban army. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.5.22–32; Diodoros. 15.63.4–15.64.6)

In addition to invading and pillaging all of Lakonike, the Theban allied army freed the Messenian helots (serfs) from their centuries long servitude to the Lakedaimonians (Spartans), founded the Messenian capital of Ithome (later called Messene), and by these acts securely established the new state of Messenia. (Diodoros 15.66–67.1; Plutarch. Agesilaos 34.1–2; Pausanias 4.26–27, 4.31.10, 4.32.1, 8.52.4, 9.14.5, 9.15.6, 10.10.5)

The defection of many Lakedaimonian perioikoi, the loss of the labour of the Messenian helots, and the loss of the fertile territory of Messenia were arguably greater blows to the Lakedaimonian state than had been the battle of Leuktra itself!

THE SECOND THEBAN CAMPAIGN INTO THE PELOPON-NESOS, 369 BCE

During the summer of 369 BCE (or possibly 368 BCE), the Eleians, Arkadians, and Argives once again joined Epameinondas and the Theban allied army. This anti-Lakedaimonian coalition campaigned in the northeast corner of the the Peloponnesos against the Sikyonians, Pelleneans of Akhaia, Epidaurians, and Korinthians. These states were supported by troops from the Lakedaimonians (Spartans), Athenians, and a small force from the Syracusan tyrant Dionysios the Elder. Nonetheless, the Sikyonians and Pelleneans defected to the Thebans. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.1.15–22, 7.2.2–3, 7.2.11–16)

Xenophon observed that this campaign was the last in which all of the anti-Lakedaimonian allies cooperated under Theban leadership. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.1.22)

THE SO-CALLED ‘TEARLESS BATTLE’, 368/367 BCE

In 368 (or possibly 367 BCE), the Arkadians and Argives—and possibly the Messenians—were defeated in southwestern Arkadia by the Lakedaimonian (Spartan) prince Arkhidamos, the son of the elderly Lakedaimonian king Agesilaos, in the so-called ‘Tearless Battle’. However, this Lakedaimonian victory was clearly inconsequential and could not have involved massive Arkadian and Argive casualties. If the Arkadians and Argives had lost the numbers alleged by ancient writers—especially the huge numbers alleged by Diodoros—, the so-called ‘Tearless Battle’ would have dwarfed the battle of Leuktra in importance and would have crippled the Arkadians and Argives for a generation! It didn’t.

Xenophon wrote that Arkhidamos was joined by troops sent by the Syracusan tyrant Dionysios the Younger and together they captured Karyai—a former Lakedaimonian perioikic town on the northeastern frontier of Lakonike—and cut the throats of all of their prisoners. From there, Arkhidamos laid waste to Parrhasia in southwestern Arkadia. However, when an army of Arkadians and Argives came to the rescue, Arkhidamos retreated back towards Lakedaimonian territory and encamped in the hills above Malea. There Kissidas, the commander of the troops sent by Dionysios, announced that the time alloted for his stay had expired and marched off toward Sparta! However, Kissidas was cut off at a narrow part of the road by the Messenians and called for Arkhidamos to come to his aid. He did so, but the Arkadians and Argives attempted to cut Arkhidamos off from his route home. On the level ground at the juncture of the roads to the Eutresians and Malea, Arkhidamos drew up his troops for battle and charged. Only a few of the enemy stood their ground and they were slain. Others were slain as they fled; many by the cavalry and the Kelts, who were amongst the troops sent by Dionysios. Clearly, Arkhidamos had masterfully caught the superior enemy army unprepared and had routed them probably before they had time to draw up in a line of battle. Arkhidamos sent news of his victory home and reported that “not even one of the Lakedaimonians died” while “pamplētheis (vast numbers) of the enemy” were slain. All of the people of Sparta wept for joy beginning with King Agesilaos, the gerontes (senators), and the ephors. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.1.28-32)

Diodoros briefly mentioned the battle incredibly calling it a “megalē makhē (great battle) against the Arkadians” in which “hyper (over) ten thousand Arkadians fell and not one Lakedaimonian”! Diodoros related the tale that the priestess at the famed oracle of Zeus at Dodona in Epeiros had advised the Lakedaimonians that the war would be a tearless one. (Diodoros. 15.72.3–4)

Plutarch simply stated that “not one fell” of Arkhidamos’ army whereas “sykhnous (many) of the opposition were killed”. Like Xenophon, Plutarch also wrote that, when the results of the victory were reported back in Sparta, the elated Lakedaimonians—including King Agesilaos—wept tears of joy! Plutarch called the victory the “so-called Adakrytos Makhē (‘Tearless Battle’)”. It would perhaps be more appropriate to call this Lakedaimonian victory the ‘Battle Without Tears of Sorrow’ as according to both Xenophon and Plutarch copious tears of joy were shed! Plutarch added perceptively that nothing demonstrated the fallen state of Lakedaimon (Sparta) so much as their excessive joy at the news of this victory. In the past, the Lakedaimonians had been famous for their unemotional response to the news of their many victories. (Plutarch. Agesilaos 33.3–5)

It seems more than likely that the goal of Arkhidamos’ expedition into Parrhasia had been to prevent the settlement and construction of the new Arkadian city of Megalopolis (Megala polis, the ‘Big City’). Clearly the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) failed to do so. Megalopolis—which was founded either shortly before or shortly after the battle—soon prospered as a bastion against Lakedaimonian imperialism right in the very vicinity in which this allegedly spectacular Lakedaimonian victory was supposed to have taken place! Typical of his pro-Lakedaimonian (Spartan) stance, Xenophon did not even allude to the foundation of Megalopolis![5]

In all probability, the Arkadians and their Peloponnesian allies lost a minor engagement, which had allowed Arkhidamos and his army to escape back home unscathed. The excessive Lakedaimonian (Spartan) joy at the news of this victory was likely due to their relief that the Lakedaimonian army had unexpectedly escaped scot-free from the dangerous situation into which Arkhidamos had blundered during his retreat! In any event, the Arkadians were unquestionably the victors in the overall campaign as they not only maintained control of all Arkadian territory but they even encroached deeply into territory that had been Lakedaimonian (Spartan) since time immemorial![6]

THE WAR BETWEEN THE ELEIANS AND THE ARKADIAN LEAGUE, 365–363 BCE

Despite their common cause against Lakedaimon (Sparta), the Arkadians and Eleians soon came to blows over territorial disputes. As mentioned above, the Lakedaimonians had stripped the Eleians of much of their territory in ca. 399–397 BCE and at the time had granted the eastern Eleian town of Lasion to the Arkadians. Following the Lakedaimonian defeat at Leuktra in 371 BCE, the Eleians had seemingly recovered some of their lost territories, but not long thereafter these territories evidently seceded from Eleian control and voluntarily joined the new Arkadian League. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 3.2.30, 7.1.26)

Unable to come to a peaceful resolution to these territorial disputes, the Eleians siezed Lasion from the Arkadian League in 365 BCE. All out war quickly followed in which the Eleians not only lost Lasion but even the sanctuary of Olympia, which the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) had left in their control in ca. 399–397 BCE. In addition, their homeland of Eleia was ravaged by the Arkadians. These losses led to a civil war in Elis in which the Eleian oligarchs drove out the democrats. The Eleian oligarchs then sought out new allies against the powerful, democratic Arkadian League and therefore allied with the oligarchs of Akhaia. The Akhaians inhabited the far northern coast of the Peloponnesos and their remoteness permitted them to often remain above the fray. However, the Akhaian oligarchs had abandoned their earlier neutrality following botched Theban and Arkadian campaigns into Akhaia roughly two years earlier in ca. 367 BCE. In a dramatic reversal of allegiances, the Eleian oligarchs also found it expedient to ally with Elis’ old enemies, the pro-oligarchical Lakedaimonians! (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.12–21, 7.4.26; Diodoros. 15.77.1–4)

Having siezed Olympia, the Arkadians hosted the 104th Olympic Games in 364 BCE. The administration of the Olympic Games had been an Eleian institution for centuries. While the games were in progress, the Eleian and Akhaian oligarchs actually attacked the Arkadians on the grounds of the sacred sanctuary of Olympia! The Arkadian democrats were supported by troops from the democracies of Argos and Athens. The Athenians had allied with the Arkadians in ca. 366 BCE without renouncing their alliance with the Lakedaimonians (Spartans). Despite some initial success, the Eleians were forced to withdraw leaving Olympia in the hands of the Arkadians. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.28–32; Diodoros. 15.78.1–3)

THE SPLINTERING OF THE ARKADIAN LEAGUE, 364–362 BCE

These Arkadian successes against the Eleians would ironically prove to be their undoing and would in short order lead not only to the splintering of the Arkadian League but to the battle of Mantinea as well! Evidently, the Arkadians would split largely along the lines of the democrats favouring Thebes and the aristocrats favouring Lakedaimon (Sparta).[7]

The problems began when the Mantineans expressed their objections to the use of Olympic treasures by the Arkadian League. These sacred funds had been looted and used to pay the Eparitoi, apparently the members of the standing army or police force of the Arkadian League.[8] In response to these reasonable Mantinean concerns, the democratic arkhontes (chief magistrates) of the Arkadian League at first summoned the Mantinean leaders before the Arkadian League assembly, which was called the Myrioi (Ten Thousand) or simply the koinon (commons). However, when they refused to appear, the arkhontes past judgement against the Mantinean leaders and sent the Eparitoi to arrest them for sowing discord! However, the Mantineans shut their gates against the Eparitoi and their leaders thereby avoided arrest. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.33)

Subsequently, the Myrioi (Ten Thousand) reconsidered their actions and voted to cease to appropriate the Olympic treasures. Only the wealthier Arkadians were then able to serve amongst the Eparitoi without pay. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.34)

Fearing that these developments might lead to an investigation of their impious and possibly criminal handling of the Olympic treasures, the Arkadian League arkhontes (chief magistrates) sent to the Thebans requesting military assistance. However, according to Xenophon, the koinon (commons) of the Arkadians sent ambassadors to Thebes to notify them to not respond to this request unless they received an official summons for military assistance from themselves. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.34–35)

At the same time, the Arkadians decided to return control of the sanctuary of Olympia to the Eleians out of respect for tradition and respect—or more likely fear—of divine law. The Arkadian League and the Eleians then concluded a peace treaty. Xenophon did not bother to mention who retained control of Lasion, the original bone of contention. However, it appears to have remained Arkadian. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.35)

THE BOTCHED ARRESTS IN TEGEA, 363 BCE

The Arkadians— presumably the Myrioi (‘Ten Thousand’, the assembly)—met in Tegea to ratify this treaty with the Eleians and afterwards many of them stayed behind to feast, drink, and ēuthymounto (make merry). The democratic Arkadian League arkhontes (chief magistrates) along with their supporters amongst the Eparitoi then began to arrest the Arkadian aristocrats who were present. This likely took place after nightfall. They were assisted by a force of 300 Boiotian hoplites, who—according to Xenophon—just happened to be in Tegea! Their principal targets were the Mantinean aristocrats. However, it turned out that most of the Mantineans had gone home after the peace conference as Mantinea was relatively close by. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.36–37)

In the morning, the Mantineans learned what had happened at Tegea and straight away notified the other Arkadian cities and advised them to put their military forces on alert. The Mantineans then sent to Tegea and demanded the release of all of the prisoners and insisted that the proper way to handle any dispute was by hearings before the koinon (commons) of the Arkadians. Of course, the Mantineans had earlier declined to cooperate with this very course of action and had, by that refusal, precipitated this crisis! (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.38)

Having failed to capture the Mantinean leaders, the Theban commander of the 300 Boiotian hoplites was in doubt how to proceed. Consequently, he promptly released all of the prisoners. The next day, this Theban officer called together all of the Arkadians in Tegea and justified his actions by claiming that he had been deceived by false reports that a Lakedaimonian (Spartan) army was on the border and was conspiring to seize Tegea. By the way, Xenophon maddeningly failed to give the name and position of this Theban. The Arkadians—apparently the Myrioi—sent ambassadors to Thebes to denounce this Theban and to demand that he be put to death for essentially an act of war much like that committed against the Thebans themselves twenty years earlier. In 382 BCE, the Lakedaimonian commander Phoibidas had unlawfully seized and garrisoned the Kadmeia, the citadel in Thebes, and had arrested the Theban democratic leader Ismenias, who was subsequently executed by the Lakedaimonians. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.39)

As I commented in my introduction, due to his partisanship, Xenophon—a staunch oligarch and supporter of the Lakedaimonians (Spartans)—was biased in his assessments. In that regard, it is without doubt significant that Thebes was a democracy and that both Epameinondas and Pelopidas were loyal supporters of their city’s government. The following examples clearly demonstrate the excessive degree to which Xenophon carried his partisanship and how it adversely affected his writing of history!

Xenophon rarely mentioned the names of the two great Theban leaders Epameinondas and Pelopidas. This is hard to justify or even to understand. For example, Xenophon did not report the victory of Pelopidas over the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) at Tegyra in Boiotia in 376/375 BCE. This Theban victory was minor due to the number of troops involved yet it was the first time in recorded history that Lakedaimonian (Spartan) hoplites had been defeated by a numerically inferior enemy in hand-to-hand combat! Leading only the 300 man Theban Sacred Band and a small force of cavalry, Pelopidas had routed two Lakedaimonian morai (divisions) of hoplites and had slain their two commanders, who were known as polemarchs. A single mora apparently numbered 500 to 600 men at this time. (Diodoros. 15.81.2; Plutarch. Pelopidas 16–17)

Incredibly Xenophon did not mention either Epameinondas or Pelopidas in his account of their momentous victory over the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) at the battle of Leuktra in 371 BCE. This Theban victory was arguably the most significant Greek battle of Xenophon’s entire lifetime and yet he disdained to record the names of either of the two victorious Theban generals! In addition, instead of crediting Epameinondas and Pelopidas for their leadership and ingenious tactics, Xenophon incredibly ascribed the Theban victory to tykhē (good fortune, fate, chance)! (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.4)

Xenophon did not mention the name of either Theban commander in his account of their historic invasion of Lakonike, the homeland of the Lakedaimonians (Spartans), during the winter of 370/369 BCE. According to Plutarch (Agesilaos 32.3–6), Lakonike had not been invaded for over 600 years! This was more than likely an exaggeration, but certainly no enemy had overran and pillaged all of Lakonike within living memory. In other words, this accomplishment of Epameinondas and Pelopidas was a really big deal worthy of note!

At least Xenophon reported the battle of Leuktra and the invasion of Lakonike. However, Xenophon disdained to even allude to the fact that Epameinondas and Pelopidas had liberated the Messenian helots (serfs) from their cruel, centuries long servitude to the Lakedaimonians (Spartans)! It certainly could not be contested by any objective commentator that this achievement by the two Thebans was worthy of note if not for its humanitarian aspect then at least for its crushing impact upon the Lakedaimonian economy. Of course, since Xenophon was a devoted partisan of the Lakedaimonians, the emancipation of the Messenian helots was not something that he could celebrate. Nonetheless, as a historian, Xenophon should have reported it!

Rather than report these earth-shaking achievements by Epameinondas and Pelopidas, Xenophon instead deemed it important to note that Epameinondas supposedly supported the unnamed Theban commander’s questionable actions in Tegea and also that Epameinondas responded to the Arkadians’ legitimate complaints with seemingly unreasonable threats of invasion! (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.40)

In a blatantly partisan appraisal, Xenophon referred to the Arkadian oligarchs as those who were “concerned about the Peloponnesos” and who saw that “the Thebans clearly wished the Peloponnesos to be weak so that it would be easy to enslave” and who “thought about the best interests of the Peloponnesos”. I must confess that it is incomprehensible to me that Xenophon apparently did not recognize that the Peloponnesians had been ‘enslaved’ by heavy-handed Lakedaimonian (Spartan) imperialism for generations! (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.5.1, 7.4.35)

Unfortunately, we do not know what were the thoughts of Xenophon’s political opponents, the democrats, nor do we know their version of these crucial events in Arkadia. However, it is reasonable to assume that Xenophon omitted facts that reflected poorly upon his beloved Lakedaimon (Sparta) and upon aristocrats, whom Xenophon tellingly called the beltistoi (most excellent), gnōrimoi (distinguished), kaloi kagathoi (beautiful/noble well-born), and kratistoi (strongest, most excellent). On the other hand, Xenophon referred to democrats as simply the dēmos (the commons, the people). It is also reasonable to assume that Xenophon also omitted facts that reflected well upon the Thebans and other democrats.

GO TO PART TWO

[1]↩ For the most part, I have tried to use the local, native spelling of names. The Mantineans called their city Mantinea. The city was called Mantinee in Ionic Greek and Mantineia in the Attic dialect. (An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis: An Investigation Conducted by The Copenhagen Polis Centre for the Danish National Research Foundation. [Edited by] Mogens Herman Hansen and Thomas Heine Nielsen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. Page 517)

[2]↩ W. K. Pritchett observed “The fundamental account of the battle of 362 B.C. derives from Xenophon, who whatever his defects as an historian, especially in presenting a clear picture, did not wilfully invent falsehoods.” (William Kendrick Pritchett. Studies in Ancient Greek Topography Part II (Battlefields). Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969. Page 70)

The other primary source for this period and for the campaign is the Siceliote (Sicilian Greek) Diodoros of Agyrion also known by his Latinized name Diodorus Siculus. Diodoros (floruit ca. 60–30 BCE) wrote roughly 300 years after the battle. His Bibliothēkēs Historikēs (Historical Library) is a valuable historical source, but is of variable quality. See: P.J. Stylianou. A Historical Commentary on Diodorus Siculus, Book 15. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. If you happen to have a copy of this book for sale at a reasonable price, please contact me by leaving a comment (see the link at the bottom of the footnotes).

Modern scholars almost universally believe that Diodoros’ account was derived from the history of Ephoros of Kyme (floruit 4th Century BCE). The ancient Greek historian Polybios of Megalopolis (12.25f.3) dismissed Ephoros’ account of the battle of Mantinea as geloios (laughable, ludicrous)! According to W. K. Pritchett, Polybios (ca. before 199–120 BCE) was “the best military historian of antiquity”. Diodoros’ account—whether derived from Ephoros or not—would certainly qualify as geloios! (William Kendrick Pritchett. Studies in Ancient Greek Topography Part II (Battlefields). Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969. Page 37).

Unfortunately, the account of this campaign given by Diodoros is largely valueless. It differs in so many details from the fuller account of Xenophon. In addition, Diodoros’ account contains obvious errors and just does not make sense in some important particulars. I have, therefore, rejected the sequence of events as well as many of the details presented by Diodoros. I have accepted a few details that do not conflict with Xenophon and that I consider to be plausible. (Diodoros. 15.82.1–15.89.2)

[3]↩ Thebes was the leading city of Boiotia. The chief officials of the Boiotian League were called the Boiotarchs. In theory there were eleven Boiotarchs elected annually from the districts of Boiotia; the city of Thebes elected two Boiotarchs (Hellēnika Oxyrhynkhia. fragment 16.3-4). However, the Lakedaimonians used the King’s Peace of 386 BCE to break up the Boiotian League in order to keep Boiotia—and Thebes in particular—weak. Following the liberation of Thebes from a Lakedaimonian garrison in late 379 BCE, the Thebans attempted to reconstitute the Boiotian League. Eight years later at the time of the battle of Leuktra in 371 BCE, there were evidentially only seven Boiotarchs. The important Boiotian cities of Orkhomenos and Thespiai were controlled by pro-Lakedaimonian factions and both refused to join the new Boiotian League. Incidentally, Pelopidas had played a leading role in the liberation of Thebes and was rewarded by being elected Boiotarch most years thereafter until his death in 364 BCE. The year 371 BCE was one of the few exceptions.

[4]↩ According to Xenophon, the Eleians lost Lepreon, Makiston, Epitalion, Letrinoi, Amphidolia, Marganeis, Phrixai, Akroreia, Lasion, and Epeion. And, of course, Xenophon wrote that, after being exiled from Athens, he had settled at Skillous near the sanctuary of Olympia in a Lakedaimonian (Spartan) colony. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 3.2.25–31; Xenophon. Anabasis 5.3.7–13)

[5]↩ Pausanias (8.27.1–8) related quite a bit about Megalopolis and noted that the city was founded a few months after the battle of Leuktra in the second year of the 102nd Olympiad (late summer 371 BCE to late summer 370 BCE). However, according to the questionable testimony of Diodoros (15.72.4), Megalopolis was founded after the so-called ‘Tearless Battle’ (ca. 368/367 BCE). According to Diodoros’ own account, this does not make any sense! Diodoros claimed the Arkadians lost 10,000 men. All of Arkadia would have been acutely underpopulated after such a staggering loss and they surely would have been unwilling to further reduce their respective populations by founding such a large new city!

[6]↩ Xenophon’s exaggeration concerning the immensity of this Lakedaimonian (Spartan) victory at the expense of the overall results of the campaign is in keeping with his pro-Lakedaimonian bias. For example, in describing the Theban invasion of Lakonike in the winter of 370/369 BCE, Xenophon completely ignored the historic liberation of the Messenian helots, the foundation of Ithome, and the establishment of the state of Messenia. Instead of recording these historic Theban achievements, Xenophon (Hellēnika 6.5.30–31) reported a ridiculously insignificant Lakedaimonian victory on the outskirts of Lakedaimon (Sparta)! This minor skirmish—just like the so-called ‘Tearless Battle’—had absolutely no impact upon the outcome of the overall campaign!

Following the ‘Tearless Battle’ (apparently later in the same year), the Argives and “hapantes (all) of the Arkadians” unsuccessfully attacked the Phleiasians in the northeast Peloponnesos. Such a campaign would not have even been possible if they had lost massive casualties in the ‘Tearless Battle’! In ca. 366 BCE, the Arkadians further flexed their muscles by ousting the tyrant Euphron from Sikyon. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.2.10, 7.3)

A few years after the so-called ‘Tearless Battle’ of ca. 368/367 BCE, the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) found it necessary to get aid from the Syracusan tyrant Dionysios the Younger in ca. 365 BCE in order to recapture the city of Sellasia in central Lakonike. Sellasia was only 25 or so kilometres northeast of Lakedaimon (Sparta) and yet it was in Arkadian hands roughly three years after the ‘Tearless Battle’! (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.12)

As another example of the Arkadian annexation of Lakedaimonian (Spartan) territory shortly after the so-called ‘Tearless Battle’, the Lakedaimonian prince Arkhidamos retook Kromnos in ca. 365 BCE. The town had previously been an integral part of northwestern Lakonike, but had obviously been annexed by the Arkadians sometime prior to ca. 365 BCE. The Lakedaimonians did not hold Kromnos for long as the Arkadians besieged the Lakedaimonian garrison of three lokhoi (companies) and forced Arkhidamos to come to their rescue. Arkhidamos was wounded and the Lakedaimonian garrison was evacuated under the cover of darkness with substantial losses. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.20–27)

At the same time as the Kromnos campaign, Xenophon noted that the Arkadians held Skiritis, an important district on the Arkadian-Lakedaimonian frontier. The Skiritai had previously supplied an elite lokhos (company) to the Lakedaimonian army. Furthermore, the Arkadian League had overwhelmed the Eleians and had taken Olympia from them in 365–364 BCE. The Arkadians had also seized the Lakedaimonian (Spartan) towns of Kyparissos and Koryphasion on the coast of western Messenia. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.13–27; Diodoros 15.77.4)

All of this was accomplished within a mere three years of the unquestionably inconsequential ‘Tearless Battle’ and would have been impossible if the Arkadians had suffered massive casualties in that battle. There can be little doubt that Xenophon greatly exaggerated the losses in this battle and was subsequently followed in doing so by other ancient writers. In all fairness to Xenophon, he only stated that “pamplētheis (vast numbers) of the enemy” were slain. Pamplētheis is a subjective term. How many are ‘vast numbers’? Would Xenophon have considered 200 dead to have been ‘vast numbers’ in the circumstances? Furthermore, Xenophon and other ancient writers were silent about the consequences of this Lakedaimonian victory. In fact, the victory was so minor that there were no significant consequences other than the Lakedaimonians escaping with their lives! It was Diodoros who was largely responsible for the hyperbole regarding this battle claiming that there were over 10,000 Arkadian dead.

[7]↩ The aristocrats and democrats of Mantinea remarkably avoided stasis (sedition, discord, civil war). Apparently the two sides lived side by side peacefully and did not turn against each other as a result of the subsequent hostilities. The Tegeatans, on the other hand, had executed their oligarchs in 371/370 BCE and “peri (about) 800” of their supporters had fled into exile. The following year, “peri (about) 400 of the youngest of the Tegeatan exiles” were slain at Oion by the Arkadians when they invaded Lakonike during the winter of 370/369 BCE. As a result, the Tegeatans remained steadfast democrats. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.5.9–10, 6.5.24–26)

[8]↩ The only substantive mention of the Eparitoi was by Xenophon, who did not bother to explain who they were! Diodoros (15.62.2, 15.67.2) mentioned a group of 5,000 so-called epilektoi (‘chosen’) commanded by Lykomedes of Mantinea during the winter of 370/369 BCE prior to the historic invasion of Lakonike and in 369 BCE at Pellana following the invasion of Lakonike. The Eparitoi are often equated with the 5,000 epilektoi by modern authors. However, there is no overlap where Xenophon referred to the Eparitoi at the same time that Diodoros referred to the epilektoi. In addition, Xenophon seems to refer to a smaller body though he may have been referring to a part of the Eparitoi rather than to the whole body. In two references to the Eparitoi, Xenophon described them as attempting to make arrests. This certainly sounds like a small body of policemen—or military police in modern parlance—rather than a large body of soldiers. Therefore, the equation of the Eparitoi with the 5,000 epilektoi is problematic. The only other surviving ancient author to have mentioned the Eparitoi was Stephanos of Byzantion (floruit ca. 6th Century CE). Stephanos wrote “Eparitai, an ethnos (people) of Arkadia.” and he gave Xenophon, Ephoros, and Androtion as his sources. Unfortunately, the works of neither of the 4th Century BCE writers Ephoros of Kyme nor Androtion of Athens have survived. Stephanos’ indentification of the Eparitai as an ethnos is undoubtedly wrong. Eparitoi was apparently an Arkadian word. It’s meaning is unknown though those scholars who equate the Eparitoi with the epilektoi assume that the word means ‘chosen’ in the Arkadian dialect.

If you encounter a word or spelling with which you are unfamiliar, be sure to check the glossaries (see the links on the right under Reference Aids).

You may find the following timeline useful. If you have a large enough screen, I suggest that you place the timeline window side by side with this window. To open the timeline in a separate window on a Mac, hold down the ‘Control’ key while clicking on the link.

|

| Ancient Greece in 362 BCE. |

INTRODUCTION

During the Greek Classical Age (ca. 500–323 BCE), there were two famous battles fought in the vicinity of the Arkadian city of Mantinea.[1] The first was a Lakedaimonian (Spartan) victory over a coalition consisting of the Argives, Athenians, and Mantineans in 418 BCE during the Peloponnesian War. The victorious commander was the Lakedaimonian king Agis II (reigned 427/426–401/400 BCE). (Thoukydides. 5.64–74)

The second famous battle fought near Mantinea was a victory by the Thebans and their allies in 362 BCE. The victorious general was Epameinondas of Thebes. His opponents were the the Lakedaimonians (Spartans), Athenians, Eleians, Akhaians, Mantineans, and a few other Arkadians.

The ancient accounts of this latter campaign are diverse and contradictory as are the modern retellings. The narrative of Xenophon of Athens in the Hellēnika is the only contemporary account and is also by far the most detailed account. It was, moreover, a record of military operations by an experienced military man. In addition, Xenophon was closely associated with both the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) and Athenians, two of the losing participants in the battle of Mantinea. Xenophon was a lover of all things Spartan and was a long-time acquaintance of the elderly Lakedaimonian king Agesilaos II (reigned ca. 401/400–360/359 BCE), the younger half-brother of Agis II. It is noteworthy that Xenophon’s two sons—Gryllos and Diodoros—were both educated in Lakedaimon (Sparta) and both also fought in the Athenian army at the battle of Mantinea. As a result of all of these factors, Xenophon would have had first hand knowledge of many details that would have been unknown to later historians. Unfortunately, due to his blatant partisanship on behalf of oligarchs and Lakedaimon (Sparta), Xenophon is notorious for his omissions and also for his biased assessments. The historical ‘facts’ that Xenophon recorded are nonetheless rarely contested. Therefore, I have for the most part followed Xenophon’s version of the events.[2]

|

| The Battlefield of Mantinea, Arkadia, Greece. (Image compliments of www.utexas.edu) |

THE PRELUDE TO THE BATTLE

In 371 BCE—nine years prior to the battle of Mantinea—the Thebans had decisively defeated the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) at the battle of Leuktra in Boiotia. The Thebans were led by Epameinondas, who was one of the Boiotarchs, and by Pelopidas, who was the commander of the 300 man Theban Sacred Band.[3] The battle of Leuktra was decisive in the sense that it forever shattered the myth of Lakedaimonian (Spartan) invincibility and also inflicted a severe blow to Lakedaimonian manpower. Though it was not immediately obvious, the battle of Leuktra in 371 BCE would sound the death knell for the Lakedaimonian hegemony of Greece. On the other hand, the battle of Mantinea in 362 BCE would not be nearly as decisive on the battlefield itself and yet it would mark the end of Lakedaimon (Sparta) as a major power, a process that had begun in earnest at Leuktra.

In the years immediately following the momentous Lakedaimonian (Spartan) defeat at Leuktra, many former Lakedaimonian allies defected to the victorious Thebans. It was this loss of so many of their allies and subjects—who were no longer in awe and fear of the ‘invincible’ Spartans—that eventually brought an end to the era of Lakedaimonian hegemony. Ironically, the Lakedaimonians did gain one major new ally: Athens. The Athenians had been defeated by the Lakedaimonians in the Peloponnesian War (ca. 431–404 BCE), but in 371 BCE they were fearful of the growing power of nearby Thebes and allied with the Lakedaimonians in hopes of maintaining a balance of power. As for the early Peloponnesian defectors from the Lakedaimonians, the two most prominent were the Eleians and Arkadians.

THE ELEIANS AND LAKEDAIMONIAN IMPERIALISM

In ca. 399–397 BCE—nearly three decades prior to the battle of Leuktra—the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) had invaded Eleia (the homeland territory of Elis) and had ‘liberated’ many of the towns of Triphylia and Eleia from Eleian jurisdiction. The war had begun when the Eleians had banned the Lakedaimonians from the Olympic Games—perhaps the 95th Olympics in 400 BCE—due to some unknown adjudication against the Lakedaimonians. The Eleians had also offended the Lakedaimonians by preventing the Lakedaimonian king Agis II from sacrificing to Zeus at Olympia. The Eleians claimed that it was contrary to custom for them to allow a sacrifice on behalf of a victory against other Greeks. All in all, the Lakedaimonians considered that the Eleians had become far too independent-minded following the end of the Peloponnesian War (ca. 431–404 BCE) and had forgotten their subservient relationship. The Lakedaimonians, therefore, had punished the Eleans by stripping them of much of their territory and had forced them to once again become obedient Lakedaimonian allies.[4] (Xenophon. Hellēnika 3.2.23–31)

After the Lakedaimonian (Spartan) defeat in the battle of Leuktra, the Athenians brokered a peace treaty in late 371 BCE. As a result of their loss of territory in ca. 399–397 BCE, the Eleians declined to sign this treaty as it preserved the status quo. The Eleians instead reaffiirmed their claim to ownership of Marganeis, Skillous, and Triphylia and consequently refused to recognize their autonomy under the terms of this common peace. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.5.1–3)

THE ARKADIANS AND LAKEDAIMONIAN IMPERIALISM

At the conclusion of the Korinthian War (ca. 395–386 BCE), the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) decided to make an example of the Arkadian city of Mantinea in order to deter their allies from thoughts of independence. The Mantineans had incurred the Lakedaimonians’ displeasure by sending grain to Argos while the Argives were at war with Lakedaimon and also by claiming that they could not serve in several Lakedaimonian campaigns due to an ekekheiria (armistice or holiday). Additionally, when the Mantineans did join in Lakedaimonian expeditions, the Lakedaimonians considered that the Mantineans were serving poorly. In 385 BCE—fourteen years prior to the battle of Leuktra—the Lakedaimonian king Agesipolis I (reigned 395–380 BCE) besieged Mantinea and compelled the Mantineans to surrender by diverting a river against the city’s walls. The Lakedaimonians then forcibly subjected the Arkadians of Mantinea to dioikismos (dispersal to villages) and exiled their democratic leaders, whom Xenophon called “troublesome demagogues”. This was done in contravention of the King’s Peace of 386 BCE, which had guaranteed autonomy to each and every Greek city and for which the Lakedaimonians themselves had been the prime movers! (Xenophon. Hellēnika 5.2.1–7; Diodoros. 15.5, 15.12)

Incidentally, Pelopidas and Epameinondas were two young Thebans—both probably around 30 years old—dutifully serving as hoplites in the Lakedaimonian allied army during the attack on Mantinea by Agesipolis in 385 BCE. In the fighting, Epameinondas was said to have saved the life of his friend Pelopidas. (Plutarch. Pelopidas 4.4–5)

Following the Lakedaimonian (Spartan) defeat at Leuktra in 371 BCE, the Mantineans took the opportunity to reverse their humiliation at the hands of the Lakedaimonians. The Mantineans synoikized (merged from villages into a city) and—despite the not so veiled threats of the Lakedaimonian king Agesilaos—began to build city walls. These actions were designed to ensure their autonomy by giving the Mantineans the ability to defend themselves from behind fortifications. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.5.3–5)

Mantinea, incidentally, was one of the two most important cities of Arkadia. The other was Tegea in southeastern Arkadia. While the Mantineans were busy rebuilding their city, the Tegeatan democrats siezed power in Tegea with the assistance of the Mantineans and executed the pro-Lakedaimonian oligarchs of Tegea. Their remaining aristocratic followers fled into exile to Lakedaimon. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.5.6–9)

At the same time, many of the Arkadians began to organize with the intention of forming a democratic koinon (league). The Arkadians who were so inclined gathered together at Asea on Arkadia’s southern border. This democratic movement was a major threat to Lakedaimonian (Spartan) control, which was based on supporting oligarchies and preventing the formation of larger states. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.5.6–12)

|

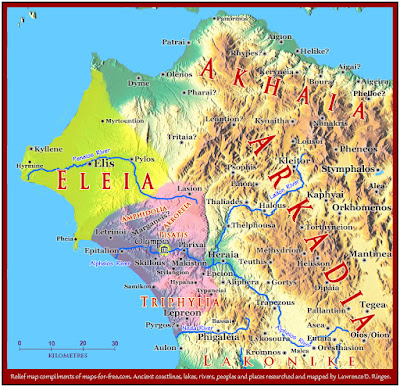

| Peloponnesos in 370 BCE. Note the large extent of Lakonike, the Lakedaimonian (Spartan) homeland. |

THE ELEIANS, ARKADIANS, AND ARGIVES JOIN FORCES AGAINST THE LAKEDAIMONIANS, 370 BCE

In response to these events, the Lakedaimonian (Spartan) king Agesilaos invaded Arkadia in late 370 BCE on the absurd pretence that the Mantineans had violated the peace by interfering in the civil war in Tegea. Agesilaos advanced to Mantinea and was shadowed by the nascent Arkadian League army from Asea. At Mantinea, Agesilaos was unable to prevent this army from joining forces with the Mantineans along with troops from Elis and Argos. If it had not been clear before, it would have been perfectly clear at this point that the Eleians had renounced their alliance with the Lakedaimonians. Having taken up arms against the Lakedaimonians, this may have been the moment when the Eleians reclaimed at least some of their lost territories. As for Argos, it was the lone Peloponnesian state to have always maintained its independence and opposition to the Lakedaimonians. As a result, the democratic Argives no doubt joined this anti-Lakedaimonian alliance with unmitigated zeal. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.5.5, 6.5.10–12, 6.5.15–16, 6.5.19)

The Lakedaimonian (Spartan) army was reinforced by Arkadians from Heraia and Orkhomenos (a traditional enemy of nearby Mantinea) as well as Lepreatans from Triphylia and Phleiasians. However, the Eleians, Argives, and the Arkadian democrats wisely refused to give battle as they had—belatedly it would appear—summoned the Thebans to come to their aid and were awaiting their arrival. When Agesilaos realised this and considered that it was already winter, he withdrew back home as quickly as he could without his withdrawal looking like flight. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.5.11, 6.5.17–22)

THE FIRST THEBAN CAMPAIGN INTO THE PELOPONNESOS, 370/369 BCE

In the winter of 370/369 BCE, the Thebans arrived in the Peloponnesos with a large allied army from central Greece. The Thebans had spent the year following the battle of Leuktra consolidating a new coalition amongst the Boiotians, Phokians, Euboians, both (i.e. eastern and western) Lokrians, Akarnanians, Herakleots, Malians, and Thessalians. Once they arrived in the Peloponnesos, the ranks of the Theban allied army were swelled by the Eleians, Arkadians, and Argives. This massive Theban allied army then invaded Lakonike, the homeland of the Lakedaimonians (Spartans). The Theban Boiotarchs Epameinondas and Pelopidas—the victors of the battle of Leuktra in 371 BCE—were at first reluctant to invade Lakonike, but were persuaded to do so by their Peloponnesian allies as well as by some of the Lakedaimonian perioikoi (second-class citizens). This invasion was an historic event as Lakonike had not been invaded within human memory. The Arkadians, Eleians, Argives, and Thebans each led one of the four columns that invaded Lakonike. The Arkadians annihiliated the Lakedaimonian force that attempted to block their advance at Oion in Skiritis and thereby emboldened the Theban army. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.5.22–32; Diodoros. 15.63.4–15.64.6)

In addition to invading and pillaging all of Lakonike, the Theban allied army freed the Messenian helots (serfs) from their centuries long servitude to the Lakedaimonians (Spartans), founded the Messenian capital of Ithome (later called Messene), and by these acts securely established the new state of Messenia. (Diodoros 15.66–67.1; Plutarch. Agesilaos 34.1–2; Pausanias 4.26–27, 4.31.10, 4.32.1, 8.52.4, 9.14.5, 9.15.6, 10.10.5)

The defection of many Lakedaimonian perioikoi, the loss of the labour of the Messenian helots, and the loss of the fertile territory of Messenia were arguably greater blows to the Lakedaimonian state than had been the battle of Leuktra itself!

THE SECOND THEBAN CAMPAIGN INTO THE PELOPON-NESOS, 369 BCE

During the summer of 369 BCE (or possibly 368 BCE), the Eleians, Arkadians, and Argives once again joined Epameinondas and the Theban allied army. This anti-Lakedaimonian coalition campaigned in the northeast corner of the the Peloponnesos against the Sikyonians, Pelleneans of Akhaia, Epidaurians, and Korinthians. These states were supported by troops from the Lakedaimonians (Spartans), Athenians, and a small force from the Syracusan tyrant Dionysios the Elder. Nonetheless, the Sikyonians and Pelleneans defected to the Thebans. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.1.15–22, 7.2.2–3, 7.2.11–16)

Xenophon observed that this campaign was the last in which all of the anti-Lakedaimonian allies cooperated under Theban leadership. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.1.22)

THE SO-CALLED ‘TEARLESS BATTLE’, 368/367 BCE

In 368 (or possibly 367 BCE), the Arkadians and Argives—and possibly the Messenians—were defeated in southwestern Arkadia by the Lakedaimonian (Spartan) prince Arkhidamos, the son of the elderly Lakedaimonian king Agesilaos, in the so-called ‘Tearless Battle’. However, this Lakedaimonian victory was clearly inconsequential and could not have involved massive Arkadian and Argive casualties. If the Arkadians and Argives had lost the numbers alleged by ancient writers—especially the huge numbers alleged by Diodoros—, the so-called ‘Tearless Battle’ would have dwarfed the battle of Leuktra in importance and would have crippled the Arkadians and Argives for a generation! It didn’t.

Xenophon wrote that Arkhidamos was joined by troops sent by the Syracusan tyrant Dionysios the Younger and together they captured Karyai—a former Lakedaimonian perioikic town on the northeastern frontier of Lakonike—and cut the throats of all of their prisoners. From there, Arkhidamos laid waste to Parrhasia in southwestern Arkadia. However, when an army of Arkadians and Argives came to the rescue, Arkhidamos retreated back towards Lakedaimonian territory and encamped in the hills above Malea. There Kissidas, the commander of the troops sent by Dionysios, announced that the time alloted for his stay had expired and marched off toward Sparta! However, Kissidas was cut off at a narrow part of the road by the Messenians and called for Arkhidamos to come to his aid. He did so, but the Arkadians and Argives attempted to cut Arkhidamos off from his route home. On the level ground at the juncture of the roads to the Eutresians and Malea, Arkhidamos drew up his troops for battle and charged. Only a few of the enemy stood their ground and they were slain. Others were slain as they fled; many by the cavalry and the Kelts, who were amongst the troops sent by Dionysios. Clearly, Arkhidamos had masterfully caught the superior enemy army unprepared and had routed them probably before they had time to draw up in a line of battle. Arkhidamos sent news of his victory home and reported that “not even one of the Lakedaimonians died” while “pamplētheis (vast numbers) of the enemy” were slain. All of the people of Sparta wept for joy beginning with King Agesilaos, the gerontes (senators), and the ephors. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.1.28-32)

Diodoros briefly mentioned the battle incredibly calling it a “megalē makhē (great battle) against the Arkadians” in which “hyper (over) ten thousand Arkadians fell and not one Lakedaimonian”! Diodoros related the tale that the priestess at the famed oracle of Zeus at Dodona in Epeiros had advised the Lakedaimonians that the war would be a tearless one. (Diodoros. 15.72.3–4)

Plutarch simply stated that “not one fell” of Arkhidamos’ army whereas “sykhnous (many) of the opposition were killed”. Like Xenophon, Plutarch also wrote that, when the results of the victory were reported back in Sparta, the elated Lakedaimonians—including King Agesilaos—wept tears of joy! Plutarch called the victory the “so-called Adakrytos Makhē (‘Tearless Battle’)”. It would perhaps be more appropriate to call this Lakedaimonian victory the ‘Battle Without Tears of Sorrow’ as according to both Xenophon and Plutarch copious tears of joy were shed! Plutarch added perceptively that nothing demonstrated the fallen state of Lakedaimon (Sparta) so much as their excessive joy at the news of this victory. In the past, the Lakedaimonians had been famous for their unemotional response to the news of their many victories. (Plutarch. Agesilaos 33.3–5)

It seems more than likely that the goal of Arkhidamos’ expedition into Parrhasia had been to prevent the settlement and construction of the new Arkadian city of Megalopolis (Megala polis, the ‘Big City’). Clearly the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) failed to do so. Megalopolis—which was founded either shortly before or shortly after the battle—soon prospered as a bastion against Lakedaimonian imperialism right in the very vicinity in which this allegedly spectacular Lakedaimonian victory was supposed to have taken place! Typical of his pro-Lakedaimonian (Spartan) stance, Xenophon did not even allude to the foundation of Megalopolis![5]

In all probability, the Arkadians and their Peloponnesian allies lost a minor engagement, which had allowed Arkhidamos and his army to escape back home unscathed. The excessive Lakedaimonian (Spartan) joy at the news of this victory was likely due to their relief that the Lakedaimonian army had unexpectedly escaped scot-free from the dangerous situation into which Arkhidamos had blundered during his retreat! In any event, the Arkadians were unquestionably the victors in the overall campaign as they not only maintained control of all Arkadian territory but they even encroached deeply into territory that had been Lakedaimonian (Spartan) since time immemorial![6]

THE WAR BETWEEN THE ELEIANS AND THE ARKADIAN LEAGUE, 365–363 BCE

Despite their common cause against Lakedaimon (Sparta), the Arkadians and Eleians soon came to blows over territorial disputes. As mentioned above, the Lakedaimonians had stripped the Eleians of much of their territory in ca. 399–397 BCE and at the time had granted the eastern Eleian town of Lasion to the Arkadians. Following the Lakedaimonian defeat at Leuktra in 371 BCE, the Eleians had seemingly recovered some of their lost territories, but not long thereafter these territories evidently seceded from Eleian control and voluntarily joined the new Arkadian League. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 3.2.30, 7.1.26)

|

| Elis and Arkadia in ca. 365 BCE. Note the new Arkadian foundation of Megalopolis. |

Unable to come to a peaceful resolution to these territorial disputes, the Eleians siezed Lasion from the Arkadian League in 365 BCE. All out war quickly followed in which the Eleians not only lost Lasion but even the sanctuary of Olympia, which the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) had left in their control in ca. 399–397 BCE. In addition, their homeland of Eleia was ravaged by the Arkadians. These losses led to a civil war in Elis in which the Eleian oligarchs drove out the democrats. The Eleian oligarchs then sought out new allies against the powerful, democratic Arkadian League and therefore allied with the oligarchs of Akhaia. The Akhaians inhabited the far northern coast of the Peloponnesos and their remoteness permitted them to often remain above the fray. However, the Akhaian oligarchs had abandoned their earlier neutrality following botched Theban and Arkadian campaigns into Akhaia roughly two years earlier in ca. 367 BCE. In a dramatic reversal of allegiances, the Eleian oligarchs also found it expedient to ally with Elis’ old enemies, the pro-oligarchical Lakedaimonians! (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.12–21, 7.4.26; Diodoros. 15.77.1–4)

Having siezed Olympia, the Arkadians hosted the 104th Olympic Games in 364 BCE. The administration of the Olympic Games had been an Eleian institution for centuries. While the games were in progress, the Eleian and Akhaian oligarchs actually attacked the Arkadians on the grounds of the sacred sanctuary of Olympia! The Arkadian democrats were supported by troops from the democracies of Argos and Athens. The Athenians had allied with the Arkadians in ca. 366 BCE without renouncing their alliance with the Lakedaimonians (Spartans). Despite some initial success, the Eleians were forced to withdraw leaving Olympia in the hands of the Arkadians. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.28–32; Diodoros. 15.78.1–3)

|

| Model of Ancient Olympia, British Museum. In the upper centre of the photo is the temple of Zeus, which contained a gigantic statue of Zeus, which was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. (Image compliments of the Wikimedia Commons) |

THE SPLINTERING OF THE ARKADIAN LEAGUE, 364–362 BCE

These Arkadian successes against the Eleians would ironically prove to be their undoing and would in short order lead not only to the splintering of the Arkadian League but to the battle of Mantinea as well! Evidently, the Arkadians would split largely along the lines of the democrats favouring Thebes and the aristocrats favouring Lakedaimon (Sparta).[7]

The problems began when the Mantineans expressed their objections to the use of Olympic treasures by the Arkadian League. These sacred funds had been looted and used to pay the Eparitoi, apparently the members of the standing army or police force of the Arkadian League.[8] In response to these reasonable Mantinean concerns, the democratic arkhontes (chief magistrates) of the Arkadian League at first summoned the Mantinean leaders before the Arkadian League assembly, which was called the Myrioi (Ten Thousand) or simply the koinon (commons). However, when they refused to appear, the arkhontes past judgement against the Mantinean leaders and sent the Eparitoi to arrest them for sowing discord! However, the Mantineans shut their gates against the Eparitoi and their leaders thereby avoided arrest. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.33)

Subsequently, the Myrioi (Ten Thousand) reconsidered their actions and voted to cease to appropriate the Olympic treasures. Only the wealthier Arkadians were then able to serve amongst the Eparitoi without pay. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.34)

|

| Model of Ancient Olympia, British Museum. The line of treasuries are located in the top right of the photo. (Image compliments of the Wikipedia Commons.) |

Fearing that these developments might lead to an investigation of their impious and possibly criminal handling of the Olympic treasures, the Arkadian League arkhontes (chief magistrates) sent to the Thebans requesting military assistance. However, according to Xenophon, the koinon (commons) of the Arkadians sent ambassadors to Thebes to notify them to not respond to this request unless they received an official summons for military assistance from themselves. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.34–35)

At the same time, the Arkadians decided to return control of the sanctuary of Olympia to the Eleians out of respect for tradition and respect—or more likely fear—of divine law. The Arkadian League and the Eleians then concluded a peace treaty. Xenophon did not bother to mention who retained control of Lasion, the original bone of contention. However, it appears to have remained Arkadian. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.35)

THE BOTCHED ARRESTS IN TEGEA, 363 BCE

The Arkadians— presumably the Myrioi (‘Ten Thousand’, the assembly)—met in Tegea to ratify this treaty with the Eleians and afterwards many of them stayed behind to feast, drink, and ēuthymounto (make merry). The democratic Arkadian League arkhontes (chief magistrates) along with their supporters amongst the Eparitoi then began to arrest the Arkadian aristocrats who were present. This likely took place after nightfall. They were assisted by a force of 300 Boiotian hoplites, who—according to Xenophon—just happened to be in Tegea! Their principal targets were the Mantinean aristocrats. However, it turned out that most of the Mantineans had gone home after the peace conference as Mantinea was relatively close by. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.36–37)

In the morning, the Mantineans learned what had happened at Tegea and straight away notified the other Arkadian cities and advised them to put their military forces on alert. The Mantineans then sent to Tegea and demanded the release of all of the prisoners and insisted that the proper way to handle any dispute was by hearings before the koinon (commons) of the Arkadians. Of course, the Mantineans had earlier declined to cooperate with this very course of action and had, by that refusal, precipitated this crisis! (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.38)

|

| Arkadia. (Image compliments of the Wikimedia Commons.) |

Having failed to capture the Mantinean leaders, the Theban commander of the 300 Boiotian hoplites was in doubt how to proceed. Consequently, he promptly released all of the prisoners. The next day, this Theban officer called together all of the Arkadians in Tegea and justified his actions by claiming that he had been deceived by false reports that a Lakedaimonian (Spartan) army was on the border and was conspiring to seize Tegea. By the way, Xenophon maddeningly failed to give the name and position of this Theban. The Arkadians—apparently the Myrioi—sent ambassadors to Thebes to denounce this Theban and to demand that he be put to death for essentially an act of war much like that committed against the Thebans themselves twenty years earlier. In 382 BCE, the Lakedaimonian commander Phoibidas had unlawfully seized and garrisoned the Kadmeia, the citadel in Thebes, and had arrested the Theban democratic leader Ismenias, who was subsequently executed by the Lakedaimonians. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.39)

XENOPHON’S BIASED ASSESSMENT OF THE CAUSES OF THE WAR

As I commented in my introduction, due to his partisanship, Xenophon—a staunch oligarch and supporter of the Lakedaimonians (Spartans)—was biased in his assessments. In that regard, it is without doubt significant that Thebes was a democracy and that both Epameinondas and Pelopidas were loyal supporters of their city’s government. The following examples clearly demonstrate the excessive degree to which Xenophon carried his partisanship and how it adversely affected his writing of history!

Xenophon rarely mentioned the names of the two great Theban leaders Epameinondas and Pelopidas. This is hard to justify or even to understand. For example, Xenophon did not report the victory of Pelopidas over the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) at Tegyra in Boiotia in 376/375 BCE. This Theban victory was minor due to the number of troops involved yet it was the first time in recorded history that Lakedaimonian (Spartan) hoplites had been defeated by a numerically inferior enemy in hand-to-hand combat! Leading only the 300 man Theban Sacred Band and a small force of cavalry, Pelopidas had routed two Lakedaimonian morai (divisions) of hoplites and had slain their two commanders, who were known as polemarchs. A single mora apparently numbered 500 to 600 men at this time. (Diodoros. 15.81.2; Plutarch. Pelopidas 16–17)

Incredibly Xenophon did not mention either Epameinondas or Pelopidas in his account of their momentous victory over the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) at the battle of Leuktra in 371 BCE. This Theban victory was arguably the most significant Greek battle of Xenophon’s entire lifetime and yet he disdained to record the names of either of the two victorious Theban generals! In addition, instead of crediting Epameinondas and Pelopidas for their leadership and ingenious tactics, Xenophon incredibly ascribed the Theban victory to tykhē (good fortune, fate, chance)! (Xenophon. Hellēnika 6.4)

Xenophon did not mention the name of either Theban commander in his account of their historic invasion of Lakonike, the homeland of the Lakedaimonians (Spartans), during the winter of 370/369 BCE. According to Plutarch (Agesilaos 32.3–6), Lakonike had not been invaded for over 600 years! This was more than likely an exaggeration, but certainly no enemy had overran and pillaged all of Lakonike within living memory. In other words, this accomplishment of Epameinondas and Pelopidas was a really big deal worthy of note!

At least Xenophon reported the battle of Leuktra and the invasion of Lakonike. However, Xenophon disdained to even allude to the fact that Epameinondas and Pelopidas had liberated the Messenian helots (serfs) from their cruel, centuries long servitude to the Lakedaimonians (Spartans)! It certainly could not be contested by any objective commentator that this achievement by the two Thebans was worthy of note if not for its humanitarian aspect then at least for its crushing impact upon the Lakedaimonian economy. Of course, since Xenophon was a devoted partisan of the Lakedaimonians, the emancipation of the Messenian helots was not something that he could celebrate. Nonetheless, as a historian, Xenophon should have reported it!

|

| Translations by Lawrence Douglas Ringer. |

Rather than report these earth-shaking achievements by Epameinondas and Pelopidas, Xenophon instead deemed it important to note that Epameinondas supposedly supported the unnamed Theban commander’s questionable actions in Tegea and also that Epameinondas responded to the Arkadians’ legitimate complaints with seemingly unreasonable threats of invasion! (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.40)

In a blatantly partisan appraisal, Xenophon referred to the Arkadian oligarchs as those who were “concerned about the Peloponnesos” and who saw that “the Thebans clearly wished the Peloponnesos to be weak so that it would be easy to enslave” and who “thought about the best interests of the Peloponnesos”. I must confess that it is incomprehensible to me that Xenophon apparently did not recognize that the Peloponnesians had been ‘enslaved’ by heavy-handed Lakedaimonian (Spartan) imperialism for generations! (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.5.1, 7.4.35)

Unfortunately, we do not know what were the thoughts of Xenophon’s political opponents, the democrats, nor do we know their version of these crucial events in Arkadia. However, it is reasonable to assume that Xenophon omitted facts that reflected poorly upon his beloved Lakedaimon (Sparta) and upon aristocrats, whom Xenophon tellingly called the beltistoi (most excellent), gnōrimoi (distinguished), kaloi kagathoi (beautiful/noble well-born), and kratistoi (strongest, most excellent). On the other hand, Xenophon referred to democrats as simply the dēmos (the commons, the people). It is also reasonable to assume that Xenophon also omitted facts that reflected well upon the Thebans and other democrats.

GO TO PART TWO

FOOTNOTES

[1]↩ For the most part, I have tried to use the local, native spelling of names. The Mantineans called their city Mantinea. The city was called Mantinee in Ionic Greek and Mantineia in the Attic dialect. (An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis: An Investigation Conducted by The Copenhagen Polis Centre for the Danish National Research Foundation. [Edited by] Mogens Herman Hansen and Thomas Heine Nielsen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. Page 517)

[2]↩ W. K. Pritchett observed “The fundamental account of the battle of 362 B.C. derives from Xenophon, who whatever his defects as an historian, especially in presenting a clear picture, did not wilfully invent falsehoods.” (William Kendrick Pritchett. Studies in Ancient Greek Topography Part II (Battlefields). Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969. Page 70)

The other primary source for this period and for the campaign is the Siceliote (Sicilian Greek) Diodoros of Agyrion also known by his Latinized name Diodorus Siculus. Diodoros (floruit ca. 60–30 BCE) wrote roughly 300 years after the battle. His Bibliothēkēs Historikēs (Historical Library) is a valuable historical source, but is of variable quality. See: P.J. Stylianou. A Historical Commentary on Diodorus Siculus, Book 15. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. If you happen to have a copy of this book for sale at a reasonable price, please contact me by leaving a comment (see the link at the bottom of the footnotes).

Modern scholars almost universally believe that Diodoros’ account was derived from the history of Ephoros of Kyme (floruit 4th Century BCE). The ancient Greek historian Polybios of Megalopolis (12.25f.3) dismissed Ephoros’ account of the battle of Mantinea as geloios (laughable, ludicrous)! According to W. K. Pritchett, Polybios (ca. before 199–120 BCE) was “the best military historian of antiquity”. Diodoros’ account—whether derived from Ephoros or not—would certainly qualify as geloios! (William Kendrick Pritchett. Studies in Ancient Greek Topography Part II (Battlefields). Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969. Page 37).

Unfortunately, the account of this campaign given by Diodoros is largely valueless. It differs in so many details from the fuller account of Xenophon. In addition, Diodoros’ account contains obvious errors and just does not make sense in some important particulars. I have, therefore, rejected the sequence of events as well as many of the details presented by Diodoros. I have accepted a few details that do not conflict with Xenophon and that I consider to be plausible. (Diodoros. 15.82.1–15.89.2)

[3]↩ Thebes was the leading city of Boiotia. The chief officials of the Boiotian League were called the Boiotarchs. In theory there were eleven Boiotarchs elected annually from the districts of Boiotia; the city of Thebes elected two Boiotarchs (Hellēnika Oxyrhynkhia. fragment 16.3-4). However, the Lakedaimonians used the King’s Peace of 386 BCE to break up the Boiotian League in order to keep Boiotia—and Thebes in particular—weak. Following the liberation of Thebes from a Lakedaimonian garrison in late 379 BCE, the Thebans attempted to reconstitute the Boiotian League. Eight years later at the time of the battle of Leuktra in 371 BCE, there were evidentially only seven Boiotarchs. The important Boiotian cities of Orkhomenos and Thespiai were controlled by pro-Lakedaimonian factions and both refused to join the new Boiotian League. Incidentally, Pelopidas had played a leading role in the liberation of Thebes and was rewarded by being elected Boiotarch most years thereafter until his death in 364 BCE. The year 371 BCE was one of the few exceptions.

[4]↩ According to Xenophon, the Eleians lost Lepreon, Makiston, Epitalion, Letrinoi, Amphidolia, Marganeis, Phrixai, Akroreia, Lasion, and Epeion. And, of course, Xenophon wrote that, after being exiled from Athens, he had settled at Skillous near the sanctuary of Olympia in a Lakedaimonian (Spartan) colony. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 3.2.25–31; Xenophon. Anabasis 5.3.7–13)

[5]↩ Pausanias (8.27.1–8) related quite a bit about Megalopolis and noted that the city was founded a few months after the battle of Leuktra in the second year of the 102nd Olympiad (late summer 371 BCE to late summer 370 BCE). However, according to the questionable testimony of Diodoros (15.72.4), Megalopolis was founded after the so-called ‘Tearless Battle’ (ca. 368/367 BCE). According to Diodoros’ own account, this does not make any sense! Diodoros claimed the Arkadians lost 10,000 men. All of Arkadia would have been acutely underpopulated after such a staggering loss and they surely would have been unwilling to further reduce their respective populations by founding such a large new city!

[6]↩ Xenophon’s exaggeration concerning the immensity of this Lakedaimonian (Spartan) victory at the expense of the overall results of the campaign is in keeping with his pro-Lakedaimonian bias. For example, in describing the Theban invasion of Lakonike in the winter of 370/369 BCE, Xenophon completely ignored the historic liberation of the Messenian helots, the foundation of Ithome, and the establishment of the state of Messenia. Instead of recording these historic Theban achievements, Xenophon (Hellēnika 6.5.30–31) reported a ridiculously insignificant Lakedaimonian victory on the outskirts of Lakedaimon (Sparta)! This minor skirmish—just like the so-called ‘Tearless Battle’—had absolutely no impact upon the outcome of the overall campaign!

Following the ‘Tearless Battle’ (apparently later in the same year), the Argives and “hapantes (all) of the Arkadians” unsuccessfully attacked the Phleiasians in the northeast Peloponnesos. Such a campaign would not have even been possible if they had lost massive casualties in the ‘Tearless Battle’! In ca. 366 BCE, the Arkadians further flexed their muscles by ousting the tyrant Euphron from Sikyon. (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.2.10, 7.3)

A few years after the so-called ‘Tearless Battle’ of ca. 368/367 BCE, the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) found it necessary to get aid from the Syracusan tyrant Dionysios the Younger in ca. 365 BCE in order to recapture the city of Sellasia in central Lakonike. Sellasia was only 25 or so kilometres northeast of Lakedaimon (Sparta) and yet it was in Arkadian hands roughly three years after the ‘Tearless Battle’! (Xenophon. Hellēnika 7.4.12)